- Fact Sheet

The H-1B Visa Program and Its Impact on the U.S. Economy

Published

Foreign workers fill a critical need in the U.S. labor market—particularly in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. Every year, U.S. employers seeking highly skilled foreign professionals compete for the pool of H-1B visa numbers for which U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) controls the allocation. With a low statutory limit of visa numbers available, demand for H-1B visa numbers has outstripped the supply in recent years, and the cap has been reached before the year ends. Research shows that H-1B workers complement U.S. workers, fill employment gaps in many STEM occupations, and expand job opportunities for all.

This fact sheet provides an overview of the H-1B visa category and petition process, addresses some of the myths perpetuated about the H-1B visa category, and highlights the key contributions H-1B workers make to the U.S. economy.

H-1B Visa Category and the Petition Process

What is the H-1B Visa Category?

The H-1B is a temporary (nonimmigrant) visa category that allows employers to petition for highly educated foreign professionals to work in “specialty occupations” that require at least a bachelor’s degree or the equivalent. Jobs in fields such as mathematics, engineering, technology, and medical sciences often qualify. Typically, the initial duration of an H-1B visa classification is three years, which may be extended for a maximum of six years.

Before an employer can file a petition with USCIS, the employer must take steps to ensure that hiring the foreign worker will not harm U.S. workers.

-

Employers first must attest, on a labor condition application (LCA) certified by the Department of Labor (DOL), that employment of the H-1B worker will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of similarly employed U.S. workers.

-

Employers must also provide existing workers with notice of their intention to hire an H-1B worker.

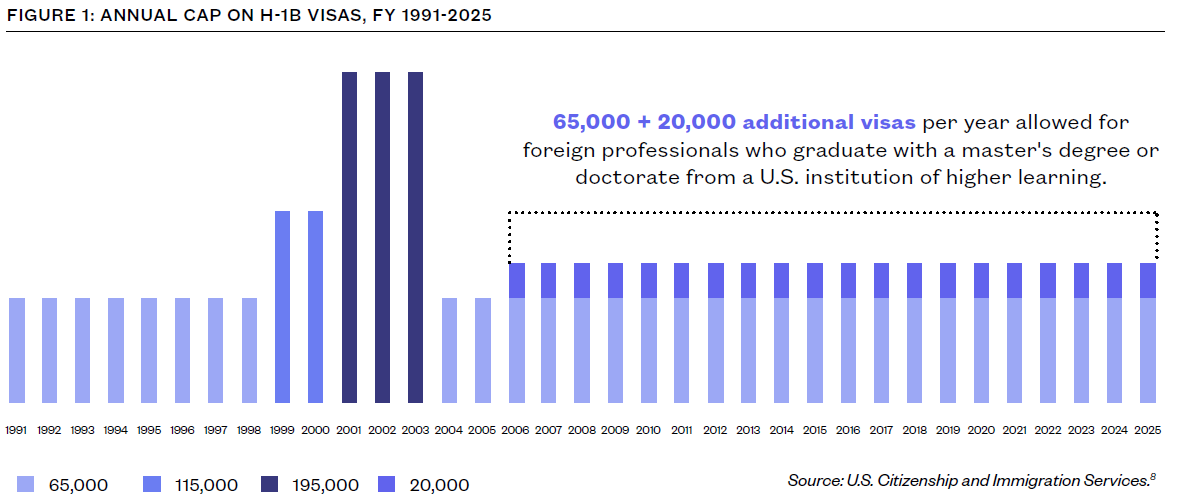

Since the category was created in 1990, Congress has limited the number of H-1Bs made available each year. The current annual statutory cap is 65,000 visas, with 20,000 additional visas for foreign professionals who graduate with a master’s degree or doctorate from a U.S. institution of higher learning (Figure 1). For Fiscal Year (FY) 2025, the cap was reached on December 2, 2024.

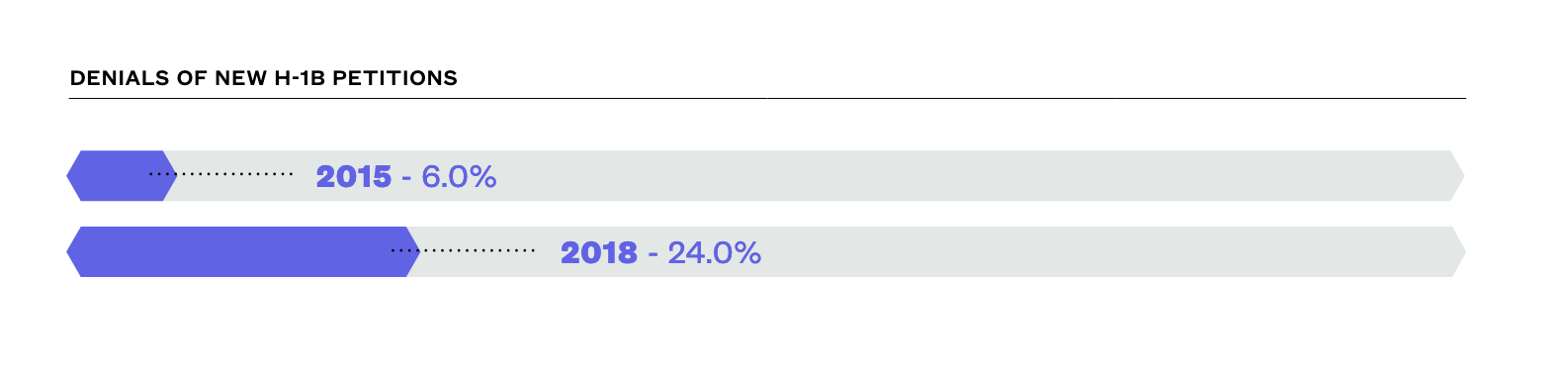

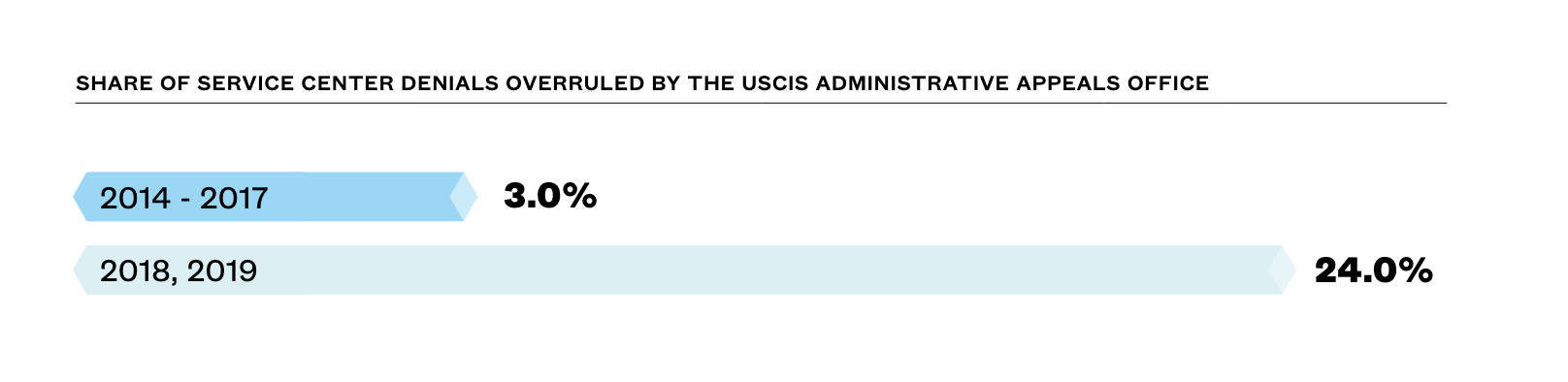

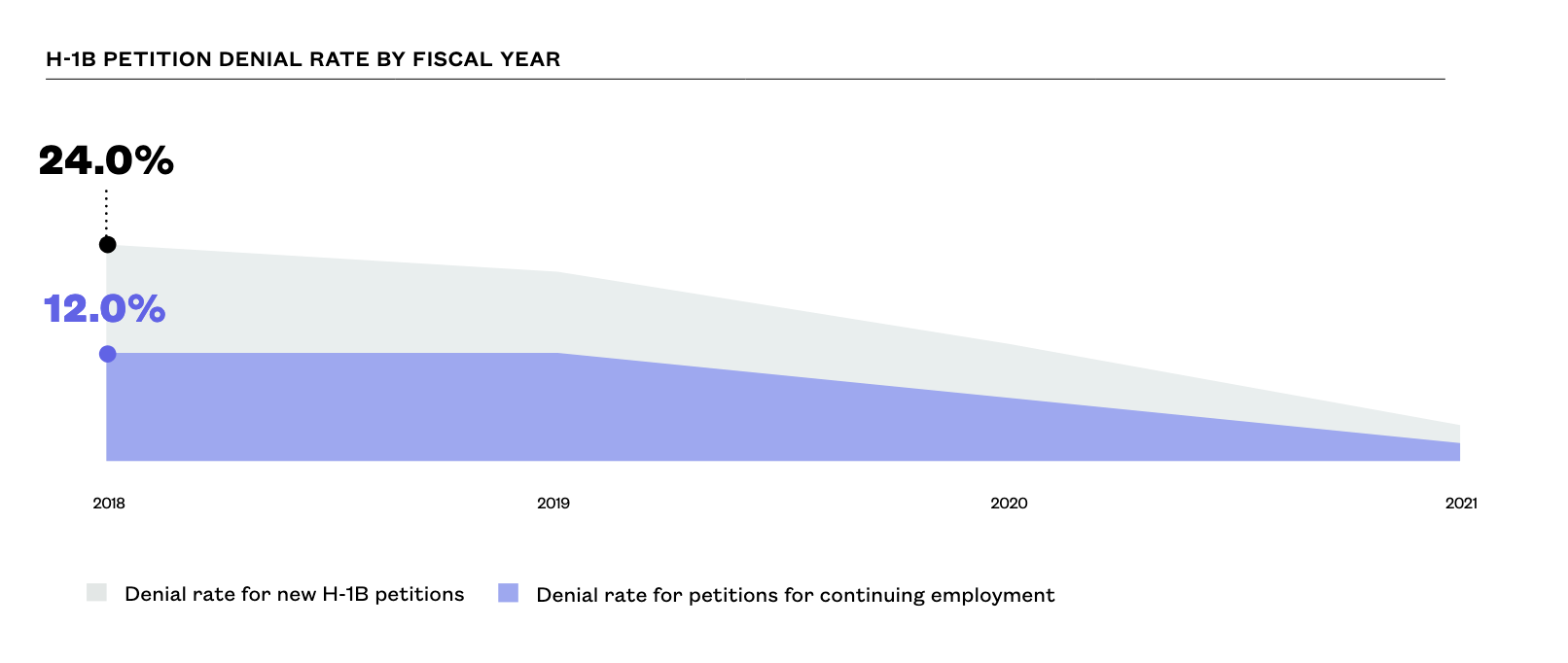

During the Trump administration, USCIS initially denied a larger percentage of H-1B petitions than in the preceding four years. But with a growing number of these denials being overturned, the denial rates decreased substantially during the latter half of FY 2020. Denials of new H-1B petitions for initial employment rose from six percent in FY 2015 to a high of 24 percent in FY 2018 before dropping to 21 percent in FY 2019, 13 percent in FY 2020, four percent in FY 2021, and only two percent in FY 2022 (the two lowest denial rates ever recorded). The denial rate for petitions for continuing employment was two percent in both FY 2022 and FY 2021, down from seven percent in FY 2020 and 12 percent in both FY 2018 and FY 2019.

H-1B Registration Process

Prior to 2020, employers were required to submit full H-1B petitions without knowing whether a visa number would be available, given that demand for visa numbers usually outstrips supply. In March 2020 (for FY 2021, beginning October 1, 2020), USCIS changed to a registration process for employers that occurs before a full petition is required. The purpose of this new process was to reduce the burden on U.S. employers, and the agency, caused by requiring employers to submit complete H-1B petitions and supporting documentation prior to knowing whether a visa number would even be available. Each year, USCIS will announce the next registration period, during which a U.S. employer must register electronically for each foreign national for whom the employer intends to file an H-1B petition.

Before USCIS required registration, if the cap was hit during the first five business days of the fiscal year, the agency conducted a lottery to determine which employers’ petitions for H-1B workers would be processed. From FY 2008 to FY 2020, the annual H-1B cap was reached within the first five business days on eight occasions.

Under the registration process, the U.S. employer must pay a fee, which is increasing from $10 to $215 for each registration submitted beginning with registrations for FY 2026. The registration includes limited information about the U.S. employer and the foreign national, in contrast to the details USCIS requires when the U.S. employer submits a full H-1B petition. While USCIS has not placed any limit on the number of registrations a U.S. employer may file, the employer must attest that it intends to file an H-1B petition on the foreign national’s behalf and cannot submit more than one registration per foreign national.

Beginning with FY 2025, USCIS changed from an employer-based to a beneficiary-centric registration system. This change followed the agency’s expression of “serious concerns” after the FY 2024 registration period about whether abuse of the system led to USCIS receiving more eligible multiple registrations (those filed on behalf of a noncitizen with more than one registration) than single registrations. With a beneficiary-centric system, the agency expects to “structurally limit the potential for bad actors to game the system because working with others to submit multiple registrations for the same beneficiary will not increase” their selection odds.

If USCIS receives more registrations than there are visa numbers available, the agency will run a lottery to determine who can file an H-1B petition. Under the beneficiary-centric system, USCIS will count the registrations “based on the number of unique beneficiaries registered” and count each beneficiary only once. USCIS will select registrations for the 65,000 visa numbers first and then for the 20,000 master’s exemption visa numbers. The agency selects more registrations than there are visa numbers available based on its projections of how many employers will file petitions and receive USCIS approval. When notifying an employer electronically that its registration was selected, the agency does not inform the employer whether any other employers filed a registration on behalf of the same beneficiary. Like the prior registration system, multiple employers with selected registrations for the same beneficiary may file H-1B petitions with USCIS. USCIS will give the U.S. employers with valid registrations for the selected beneficiary at least 90 days to file their H-1B petition. If not enough petitions are submitted to use the available visa numbers, USCIS has the option to make additional selections.

USCIS announced on April 1, 2024 that it had received enough registrations for FY 2025, and selected 114,017 beneficiaries, for whom USCIS then selected 120,603 registrations. In August 2024, USCIS conducted a second selection to reach the 65,000 regular H-1B visa number limit: 13,607 more beneficiaries (from the initial registrations) for whom USCIS selected 14,534 registrations. USCIS “saw a significant decrease in the total number of registrations submitted compared with FY 2024,” including a decrease in the number submitted on behalf of the same beneficiary. The number of unique beneficiaries and unique employers for FY 2025 was comparable to FY 2024. But the number of eligible registrations was “down dramatically:” a 38.6 percent reduction, from 758,994 in FY 2024 to 470,342 in FY 2025. USCIS also reported an average 1.06 registrations per beneficiary for FY 2025 as compared with 1.70 for FY 2024. USCIS concluded that its initial data “indicates that there were far fewer attempts to gain an unfair advantage than in prior years” which USCIS attributed “in large measure” to its implementation of the beneficiary-centric selection process. For FY 2024, USCIS conducted a second selection on July 31, 2023 (from the eligible registrations not selected initially), for a total of 188,400. For FY 2023, the agency received 483,927 registrations, decided 474,421 were eligible, and selected 127,600 registrations on March 29, 2022, which was sufficient to meet the FY 2023 cap. In contrast, for FY 2022, the agency received 308,613 registrations, decided 301,447 were eligible, but conducted three selections totaling 131,924 during 2021, because fewer selected employers than predicted actually submitted applications.

The Impact of H-1B Workers on the U.S. Economy

According to many economists, the presence of immigrant workers in the United States creates new job opportunities for native-born workers. This occurs in five ways. First, immigrant workers and native-born workers often have different skill sets, meaning that they fill different types of jobs. As a result, they complement each other in the labor market rather than competing for the exact same jobs. Second, immigrant workers spend and invest their wages in the U.S. economy, which increases consumer demand and creates new jobs. Third, businesses respond to the presence of immigrant workers and consumers by expanding their operations in the United States rather than searching for new opportunities overseas. Fourth, immigrants themselves frequently create new businesses, thereby expanding the U.S. labor market. And fifth, the new ideas and innovations developed by immigrants fuel economic growth.

The economic contributions of H-1B workers in particular may increase the employment opportunities available to native-born workers in the United States. That is why unemployment rates are relatively low in occupations that employ large numbers of H-1B workers. Many occupations for which H-1Bs are routinely requested are found within the broader category of Professional and Related Occupations. Low unemployment rates in these occupations from 2004 through 2023 (even during the COVID-19 pandemic) indicate that demand for labor exceeded the supply (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: UNEMPLOYMENT RATE IN THE UNITED STATES, 2004-2023

Similarly, a recent study found that, between 2005 and 2018, an increase in the share of workers within a particular occupation who were H-1B visa holders was associated with a decrease in the unemployment rate within that occupation. Another recent study found that restrictions on H-1B visas (such as rising denial rates) motivate U.S.-based multinational corporations to decrease the number of jobs they offer in this country. Instead, the corporations increase employment at their existing foreign affiliates or open new foreign affiliates—particularly in India, China, and Canada. A study conducted in 2019 revealed that higher rates of successful H-1B applications were positively correlated with an increased number of patents filed and patent citations. Moreover, such startups were more inclined to secure venture capital funding and achieve successful IPOs or acquisitions.

The available data also indicate that H-1B workers do not earn low wages or drag down the wages of other workers. In 2021, the median wage of an H-1B worker was $108,000, compared to $45,760 for U.S. workers in general. Moreover, between 2003 and 2021, the median wage of H-1B workers grew by 52 percent. During the same period, the median wage of all U.S. workers increased by 39 percent. In FY 2019, 78 percent of all employers who hired H-1B workers offered wages to H-1B visa holders that were higher than what the Department of Labor had determined to be the “prevailing wage” for a particular kind of job.

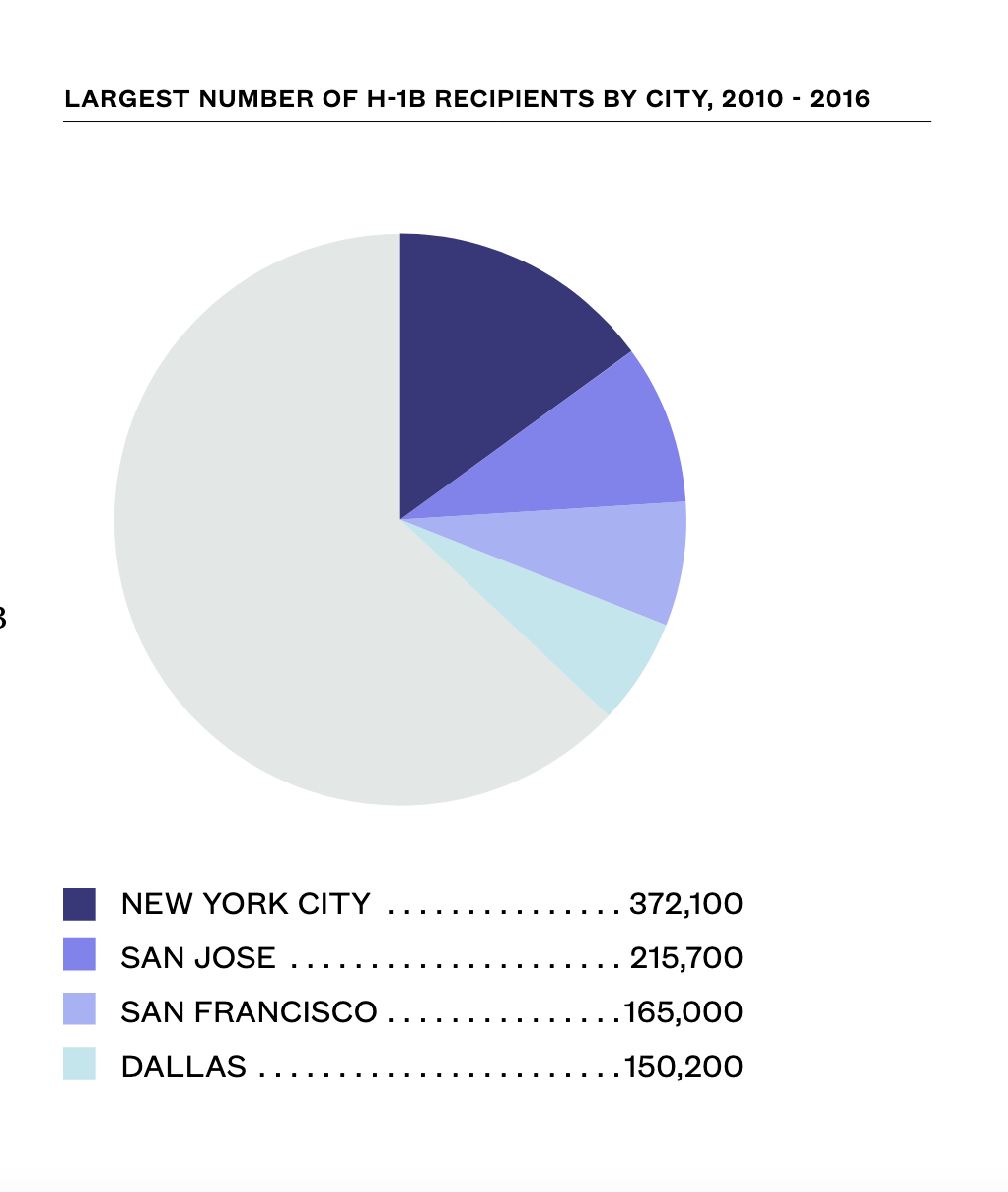

The economic benefits of the H-1B visa program are felt in communities all across the United States. For instance, from FY 2017 to FY 2022, the largest numbers of H-1B petitioners were based in the New York City metropolitan area (372,100 H-1B visa petition approvals, or 15.2 percent of all H-1B visa petition approvals in the country); followed by San Jose, California (215,700); San Francisco (165,000); and Dallas (150,200). The COVID-19 pandemic served as a reminder that the skills which H-1B workers bring with them can be critical in responding to national emergencies. For instance, between FY 2010 and FY 2019, eight U.S. companies that would later participate in the development of a COVID-19 vaccine—Gilead Sciences, Moderna Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Inovio, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron, Vir Therapeutics, and Sanofi—received approvals for 3,310 biochemists, biophysicists, chemists, and other scientists through the H-1B program. In addition, many medical doctors on the front lines of the pandemic are present in the United States on H-1B visas.

Help us fight for immigration justice!

The research is clear – immigrants are more likely to win their cases with a lawyer by their side. But very few can get attorneys.

Introducing the Immigration Justice Campaign Access Fund.

Your support sends attorneys, provides interpreters, and delivers justice.

Immigration Justice Campaign is an initiative of American Immigration Council and American Immigration Lawyers Association. The mission is to increase free legal services for immigrants navigating our complicated immigration system and leverage the voices and experiences of those most directly impacted by our country’s immigration policies to inform legal and advocacy strategies. We bring together a broad network of volunteers who provide legal assistance and advocate for due process for immigrants with a humane approach that includes universal legal representation and other community-based support for individuals during their immigration cases.