- Fact Sheet

Workers with Temporary Protected Status in Key Industries and States

Published

When the Trump administration terminated Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for hundreds of thousands of migrants from El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti (among other nations), it placed TPS holders at risk of being deported and separated from their families in the United States. It also set the stage for disruptions in the workforces of several states where the economic contributions of TPS recipients are significant.

Using data from the American Community Survey (ACS), this fact sheet estimates the likely numbers of workers with TPS from these three countries, broken down by the states in which they reside and the industries in which they are employed. To provide some measure of comparison for these figures, the estimated numbers of workers with TPS in particular states and industries are compared with the total numbers of workers of the same nationality who work in the same states and industries.

El Salvador is the largest of the affected nationalities, with the loss of TPS threatening tens of thousands of Salvadoran TPS workers in the construction, restaurant, and landscaping industries. The loss of TPS for Hondurans hits thousands of construction workers, particularly those in Texas and Florida. And, the termination of TPS for Haiti impacts thousands of restaurant and grocery store workers in Florida. This represents more than just a loss of workers in industries experiencing high levels of demand for labor. It also represents a loss of buying power that these workers possessed and the taxes they paid. The ripple effects of their removal from the United States would be felt in the local economies and communities of which they were a part.

TPS and the Trump administration

TPS is a temporary immigration status provided to nationals of specific countries that are facing an ongoing armed conflict, an environmental disaster, or other extraordinary and temporary conditions. Created by Congress in the Immigration Act of 1990, TPS provides recipients with a work permit and a stay of deportation. Despite its label as a temporary status, conditions in some countries have remained poor for so long that nationals of some TPS countries have been living in the United States with the permission of the U.S. government for many years, even decades.

As of November 2018, the Trump administration had terminated TPS designations for El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, and Sudan—although the effective dates of the terminations were delayed for 12 or 18 months, depending on the country. The decision to end the TPS designations was made despite the difficult conditions within the countries in question. In fact, U.S. embassies in Central America and Haiti let it be known that the sudden return of so many people would further destabilize countries that ranked among the most violent and impoverished in the western hemisphere. On October 3, 2018, a federal court in California blocked the administration’s termination of TPS for nationals of El Salvador, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Sudan (the only countries included in the filing of the lawsuit). This decision provided a temporary reprieve to about 300,000 people.

Workers with TPS

Immigrants who have been able to stay in the United States with TPS are more than just recipients of humanitarian generosity. With very high rates of labor market participation and long periods of residence in the United States, they have become experienced, valued employees who are well-integrated into the U.S. economy and society. As with all workers, they add value to the economy not only through the work they do, but also the goods and services they purchase in U.S. businesses, including the mortgages they maintain, as well as the taxes they pay. Among the three largest TPS populations in the country—Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Haitians—there are, according to the Center for Migration Studies, approximately 223,000 workers in a variety of industries, most notably construction, restaurants and other food services, and landscaping.

The jobs within which TPS beneficiaries tend to work are in high demand. For instance, in construction—which employs more workers with TPS than any other industry—there were roughly 278,000 job openings in September of 2018. At the same time, only 4.1 percent of construction workers around the country were unemployed that month. Likewise, in accommodation and food services (which includes restaurants and other food services), there were approximately 961,000 job openings in September 2018, while only 5.3 percent of workers in the industry were unemployed nationwide. It should be kept in mind that, according to the Congressional Budget Office, the “natural unemployment rate” (which economists use to define full employment) is 4.6 percent—meaning that 4.6 percent of workers are expected to be between jobs or to be temporarily out of work. That suggests that current levels of unemployment are extremely low in both the construction industry and the accommodation and food services industry.

Salvadorans

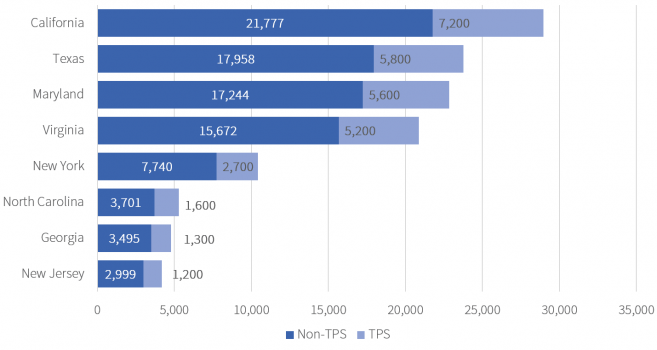

In order to qualify for TPS, Salvadorans must have lived in the United States since 2001. As a result, many Salvadoran workers have had years to cultivate their skills and become valued employees across several industries. Among the estimated 195,000 Salvadorans with TPS, roughly 171,100 recipients are working in the United States, making them the largest of the TPS populations. Although the greatest numbers of Salvadoran TPS holders are located in California, Texas, New York, Maryland, and Virginia, there are also significant numbers in New Jersey, North Carolina, Massachusetts, Nevada, and Georgia. In all of the states with a sizeable population of Salvadorans having TPS, construction is the single largest industry within which they work. Nationally, about 36,900 Salvadorans with TPS are working in construction.

- California is home to an estimated 7,200 Salvadorans with TPS who are working in construction, which amounts to one-quarter of the roughly 28,977 Salvadorans who work in construction in that state.

- Similarly, in Texas, about 5,800 Salvadorans with TPS are nearly a quarter (24 percent) of all the state’s Salvadoran construction workers.

- Salvadorans with TPS who work in construction make up comparable shares of all Salvadoran construction workers in New York (around 10,440, or 26 percent of the total), Maryland (5,600, or 25 percent), Virginia (5,200; 25 percent), and Georgia (1,300; 27 percent. The highest shares are in New Jersey (1,200; 29 percent) and North Carolina (1,600; 30 percent) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Salvadoran Construction Workers, with and without TPS, by State

Source: Robert Warren and Donald Kerwin, “A Statistical and Demographic Profile of the U.S. Temporary Protected Status Populations from El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5, no.3 (August 2017), p. 584; 2012-16 ACS.

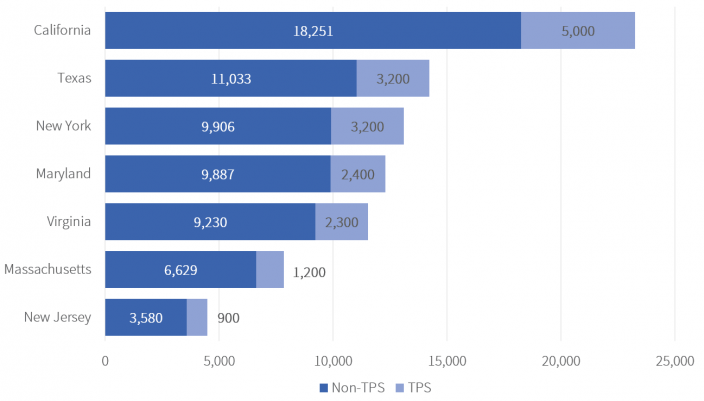

The second largest industry employing Salvadoran workers with TPS is restaurants and other food services. Approximately 22,400 Salvadorans with TPS worked in this industry nationwide. There were roughly 5,000 Salvadoran restaurant workers with TPS in California (22 percent of the approximately 23,251 Salvadoran restaurant workers in the state), 3,200 in Texas (22 percent), 3,200 in New York (24 percent), 2,400 in Maryland (20 percent), 2,300 in Virginia (20 percent), 1,200 in Massachusetts (15 percent), and 900 in New Jersey (20 percent) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Salvadoran Restaurant and Food Service Workers, with and without TPS, by State

Source: Robert Warren and Donald Kerwin, “A Statistical and Demographic Profile of the U.S. Temporary Protected Status Populations from El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5, no. 3 (August 2017), p. 584; 2012-16 ACS.

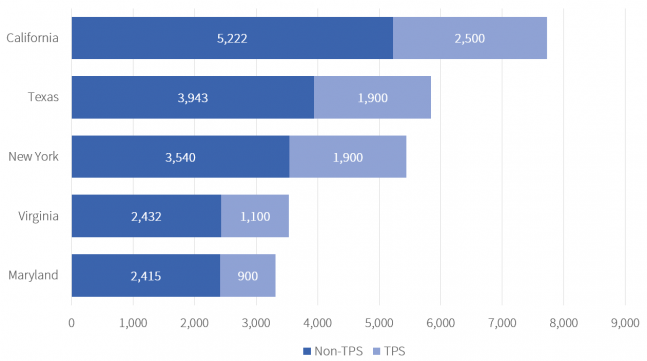

The third-most impacted industry among Salvadoran workers with TPS is landscaping, which employed roughly 11,700 Salvadoran TPS beneficiaries nationwide. About 2,500 worked in California (nearly a third, 32 percent, of the state’s Salvadoran landscaping workers), 1,900 in Texas (33 percent), 1,900 in New York (35 percent), 1,100 in Virginia (31 percent), and 900 in Maryland (27 percent) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Salvadoran Landscaping Workers, with and without TPS, by State

Source: Robert Warren and Donald Kerwin, “A Statistical and Demographic Profile of the U.S. Temporary Protected Status Populations from El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5, no. 3 (August 2017), p. 584; 2012-16 ACS.

Hondurans

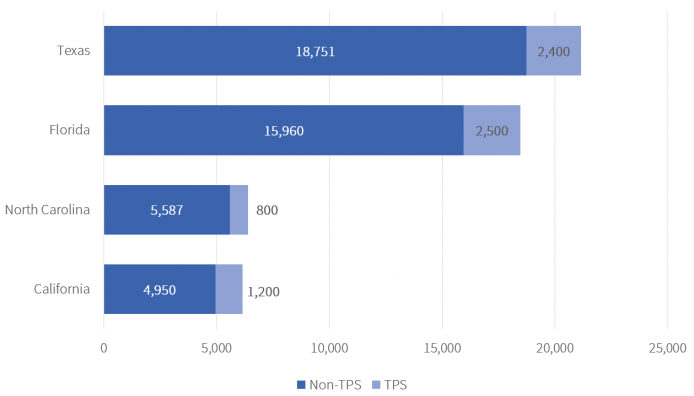

There are about 48,500 Honduran workers with TPS nationwide, and they are found primarily in Texas, Florida, and California—plus smaller numbers in North Carolina. As is the case of Salvadoran TPS beneficiaries, construction is the single biggest employer. Approximately 13,700 Honduran TPS holders nationwide work in the construction industry and there are around 2,500 in Florida (14 percent of all Honduran construction workers in the state), 2,400 in Texas (11 percent), and 1,200 in California (20 percent) (Figure 4). The number of Honduran TPS holders in other industries are generally too small to produce reliable estimates. This is the case for restaurants and other food services, landscaping, and hospitals.

Figure 4: Honduran Construction Workers, with and without TPS, by State

Source: Robert Warren and Donald Kerwin, “A Statistical and Demographic Profile of the U.S. Temporary Protected Status Populations from El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5, no. 3 (August 2017), p. 584; 2012-16 ACS.

Haitians

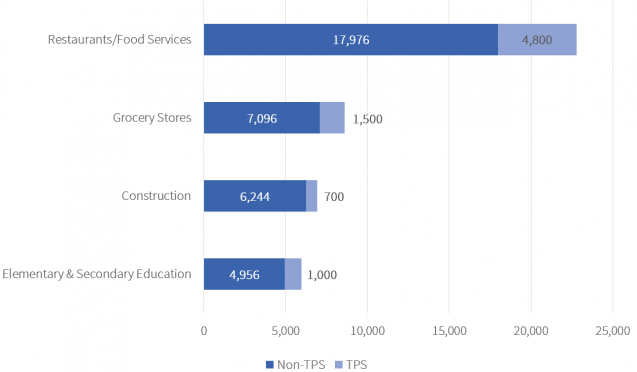

Haitian workers with TPS number roughly 38,600 nationwide. Nearly three-quarters of these workers live in Florida (20,900) and New York (6,900), but only in Florida are there sufficient numbers to allow reliable estimates of how many are employed in what industries. In Florida, most TPS beneficiaries from Haiti have jobs in restaurants and other food services (approximately 4,800, or 21 percent of all Haitians in that industry), followed by grocery stores (1,500; 17 percent), elementary and secondary education (1,000; 17 percent), and construction (700; 10 percent) (Figure 6). It should be noted that the category “elementary and secondary education” includes teachers, administrators, and support personnel.

Figure 5: Haitian Workers with and without TPS, by Industry, Florida

Source: Robert Warren and Donald Kerwin, “A Statistical and Demographic Profile of the U.S. Temporary Protected Status Populations from El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5, no. 3 (August 2017), p. 584; 2012-16 ACS.

The Economic Impact of Ending TPS

Ending TPS for migrants from El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti would not only put families at risk of separation through the deportation of TPS holders, but could trigger economic problems in the United States as well. All workers—be they TPS beneficiaries or native-born—do not simply “fill” jobs; they create jobs, too. They spend most of their wages on goods and services purchased from U.S. businesses. For instance, TPS recipients from El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti live in 206,000 households, of which nearly a third (61,100) have mortgages. In addition, a portion of workers’ wages serves as tax revenue for federal, state, and local governments. This economic activity supports the jobs of other workers. In other words, the removal of hundreds of thousands of TPS beneficiaries from the labor force would entail more than just the loss of whatever their particular work product might have been. It would also entail the loss of hundreds of thousands of consumers and taxpayers.

A report from the Immigrant Legal Resource Center estimated several of the economic costs that would be associated with expelling Salvadoran, Honduran, and Haitian TPS recipients from the United States. Losing so many workers, whose wages would no longer be flowing into the U.S. economy, would represent a loss of $4.5 billion in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per year. Plus, over the course of a decade, Social Security and Medicare would miss out on $6.9 billion in contributions. Moreover, deporting so many people would cost approximately $3.1 billion. Lay-offs alone would impose $967 million in turnover costs on the employers who had hired workers with TPS, but then had to let them go and search for new workers.

Methodology

Estimates of workers with TPS were calculated by Rob Paral and Associates and are derived from information published by the Center for Migration Studies (CMS). The CMS estimates are based on its analysis of the American Community Survey (ACS), in which CMS identifies immigrants by their likely immigration status. CMS used its modified ACS data to identify likely TPS recipients and controlled its estimates to match national administration data totals compiled by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and reported by the Congressional Research Service.

CMS published state-level totals of TPS recipients: (for El Salvador) California, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Texas and Virginia; (for Honduras) California, Florida, North Carolina and Texas; and (for Haiti) Florida and New York. These state-level estimates were furthermore published for specific industry groups.

The CMS state-level estimates were apportioned to states and industries in the following manner:

- Using the Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) of the ACS for years 2012-2016, proxy populations for each national-origin group were created that consisted of persons who were not U.S. citizens and who entered the U.S. prior to 2002 (El Salvador), prior to 2000 (Honduras) and prior to 2012 (Haiti). These dates correspond to the “continuous physical presence” requirement of TPS recipients.

- The proxy populations were tabulated by state and industrial category of employment. The resulting distributions by state and industry were used to apportion the national CMS estimates to local levels.

- The findings are estimates and should be interpreted with care. The data are helpful to understand the scope and distribution of TPS recipients, and to highlight where these workers are likely concentrated and where their impact is more likely to be felt. Specific categories with only a few hundred persons reported should be understood to potentially have wide variation from the actual locations and jobs of TPS recipients.

- Final estimates have been rounded to the nearest thousand.

Estimates of the total numbers of Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Haitians working in particular industries in particular states were calculated by the American Immigration Council using the 2012-2016 ACS.

Help us fight for immigration justice!

The research is clear – immigrants are more likely to win their cases with a lawyer by their side. But very few can get attorneys.

Introducing the Immigration Justice Campaign Access Fund.

Your support sends attorneys, provides interpreters, and delivers justice.

Immigration Justice Campaign is an initiative of American Immigration Council and American Immigration Lawyers Association. The mission is to increase free legal services for immigrants navigating our complicated immigration system and leverage the voices and experiences of those most directly impacted by our country’s immigration policies to inform legal and advocacy strategies. We bring together a broad network of volunteers who provide legal assistance and advocate for due process for immigrants with a humane approach that includes universal legal representation and other community-based support for individuals during their immigration cases.