- Fact Sheet

The Dream Act: An Overview

Published

The Dream Act would permanently protect certain immigrants who came to the United States as children but are vulnerable to deportation. This fact sheet provides an overview of the most recent version of the Dream Act and similar legislative proposals.

The Dream Act

The first version of the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act was introduced in 2001. In part because of the publicity around that bill, young undocumented immigrants have been referred to as “Dreamers.” Over the last 20 years, at least 11 versions of the Dream Act have been introduced in Congress. While the various versions of the bill have contained some key differences, they all would have provided a pathway to legal status for undocumented people who came to this country as children. Some versions have garnered as many as 48 co-sponsors in the U.S. Senate and 152 in the House of Representatives.

Despite bipartisan support for each iteration of the bill, none have become law. To date, the 2010 bill came closest to full passage when it passed the House but fell just five votes short of the 60 needed to proceed in the Senate.

Current Federal Legislative Proposals

There are two versions of the Dream Act currently before Congress: the Dream Act of 2021 (S. 264) and a version of the Dream Act that is incorporated into a larger bill known as the Dream and Promise Act of 2021 (H.R. 6).

The Dream Act of 2021 was introduced on February 4, 2021 in the Senate by Senators Dick Durbin and Lindsey Graham. The two senators introduced identical legislation in the previous two sessions of Congress.

The Dream and Promise Act of 2021 was introduced on March 3, 2021 in the House by Representative Lucille Roybal-Allard.

Both bills would provide path to citizenship for Dreamers. H.R. 6 would also provide a path to citizenship to beneficiaries of two humanitarian programs: Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and Deferred Enforced Departure (DED).

What Would the Dream Act Do?

Both versions of the Dream Act would provide current, former, and future undocumented high-school graduates and GED recipients a pathway to U.S. citizenship through college, work, or the armed services. The bills outline a three-step process, summarized below.

Step 1: Conditional Permanent Residence

An individual would be eligible to obtain conditional permanent resident (CPR) status, which includes work authorization, if the person has Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) or meets all of the following requirements:

- Came to the United States as a child.

- Has been admitted to an institution of higher education, has graduated high school or obtained a GED, or is currently enrolled in secondary school or a program assisting students to obtain a high school diploma or GED.

- Has not participated in the persecution of another person.

- Has not been convicted of certain crimes.

Under the terms of the bills, the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) can issue waivers of certain criminal offenses for humanitarian purposes, for family unity, or when the waiver is otherwise in the public interest.

Step 2: Lawful Permanent Residence

Anyone who maintains CPR status could obtain lawful permanent residence (LPR status or a “green card”) by satisfying one of the following requirements.

- Higher education: the person has acquired a degree from an institution of higher education or has completed at least two years, in good standing, in a program for a bachelor’s degree or higher degree in the United States.

- Military service: the person completed at least two years of military service with an honorable discharge, if discharged.

- Work: the person demonstrated employment over a total period of three years and at least 75 percent of that time the individual had employment authorization, with exceptions for those enrolled in higher education or technical school.

Individuals who cannot meet one of these requirements could apply for a “hardship waiver” if the applicant is a person with a disability; a full-time caregiver; or for whom removal would cause extreme hardship to themselves or a spouse, parent, or child who is a national or lawful permanent resident of the United States.

Step 3: Naturalization

After maintaining LPR status for five years, an individual can generally apply to become a U.S. citizen through the normal naturalization process.

Who Would Benefit From the Dream Act and H.R. 6?

The Migration Policy Institute estimates that approximately 2 million Dreamers would qualify for conditional permanent resident status under S. 264. 1.7 million of these are likely to obtain the qualifications necessary for the removal of the conditions on this status. Almost 1 million more Dreamers could become eligible for conditional permanent resident status if they enroll in school.

3 million Dreamers meet the age at entry and educational requirements for conditional permanent resident status under H.R. 6. 2.5 million of are likely to obtain the qualifications necessary for the removal of the conditions on this status. 1.1 million more Dreamers could become eligible for conditional permanent resident status if they enroll in school. Another 400,000 people meet the criteria to adjust to legal permanent residence based on their eligibility for TPS or DED.

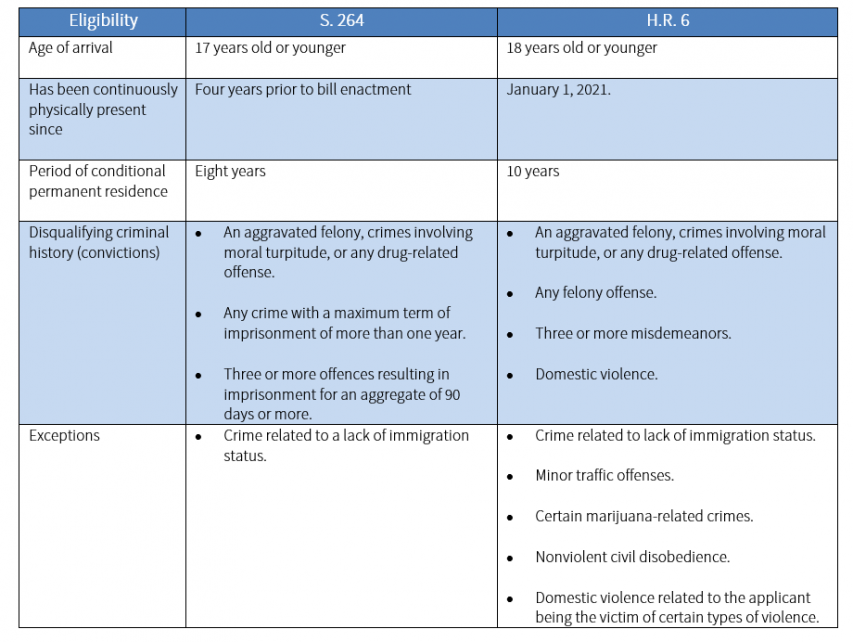

Key Differences between S. 264 and H.R. 6

The two bills have some significant differences, which are compared below.

Secondary Review Process in H.R. 6

In additional to the criminal bars listed above, H.R. 6 contains a secondary review process that would allow DHS to deny applications from individuals deemed to be threats to public safety and those who have participated within a gang in the last five years.

DHS would be allowed to conduct a secondary review of an application if the person has been convicted of any misdemeanor that is punishable by more than 30 days in jail, with exceptions as referenced above. A person is also subject to secondary review if the person has been the subject of a juvenile delinquency judgment and had to spend time in a detention facility. If DHS determines that the person is a threat to public safety, they can then deny the application.

DHS can also deny the application of a person that it determines has participated in a gang within the past five years. These determinations would be partially based on ICE databases known for being unreliable.

On February 8, over 270 organizations sent a letter to Congress expressing that the broad criminal bars and secondary review process included in the 2019 and now also in the 2021 bill would deny many otherwise eligible people, slow down implementation, and replicate the racial bias in the criminal justice system.

H.R. 6 also includes several provisions that are not included in S. 264. The bill:

- Repeals the 1996 law which penalizes states that grant in-state tuition to undocumented students on the basis of residency and allows Dreamers to access federal financial aid.

- Allows eligible Dreamers deported under the Trump administration to apply for relief from outside the country.

Help us fight for immigration justice!

The research is clear – immigrants are more likely to win their cases with a lawyer by their side. But very few can get attorneys.

Introducing the Immigration Justice Campaign Access Fund.

Your support sends attorneys, provides interpreters, and delivers justice.

Immigration Justice Campaign is an initiative of American Immigration Council and American Immigration Lawyers Association. The mission is to increase free legal services for immigrants navigating our complicated immigration system and leverage the voices and experiences of those most directly impacted by our country’s immigration policies to inform legal and advocacy strategies. We bring together a broad network of volunteers who provide legal assistance and advocate for due process for immigrants with a humane approach that includes universal legal representation and other community-based support for individuals during their immigration cases.