- Fact Sheet

Built to Last: How Immigration Reform Can Deter Unauthorized Immigration

Published

One of the explicit goals of the “Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act’’ (S.744) is to curtail future flows of unauthorized immigration by correcting some of the flaws of the current legal immigration system. To that end, it establishes an updated system of legal immigration that, in principle, seeks to match the country’s economic and labor needs while respecting principles of family unification.

The regulation of future flows is key to the success of immigration reform because the economy is one of the primary drivers of illegal immigration. Critics of reform, including those challenging S.744, argue that immigration reform which legalizes the current undocumented population or that does not mandate a biometric entry/exit system for new workers will fail because it will lead to increased flows of illegal immigration in the future. The argument usually used is that this happened after the Immigration Control and Reform Act (IRCA) was implemented in 1986, and that this would happen again were a new reform that includes a comprehensive legalization package to be passed.

These arguments, however, are flawed. In fact, they fail to address IRCA’s shortcomings by proposing a limited interpretation that points to the presumed association between legalization and the increase of future illegal entry of migrants. But the problem with IRCA, as shown by several studies, did not reside in its legalization component. The issue, on the contrary, was largely based on IRCA’s failure to realistically regulate future immigrant flows based on an accurate and pragmatic assessment of the country’s needs.

S.744, on the other hand, provides an invaluable opportunity to keep undocumented immigration in check. By providing stronger and more flexible channels for legal migration, while also addressing some of the obstacles that currently clog the immigration system, S.744 is poised to significantly curb illegal immigration going forward.

How did IRCA handle undocumented immigration?

- IRCA created a legalization program for approximately 2.7 million undocumented immigrants who had entered the country before January 1, 1982 and met certain requirements (i.e., application within 18 months, continuous residence, and admission of unlawful presence).

- In conjunction with the legalization program, IRCA required employers to verify workers’ eligibility to work legally and made it illegal for employers to knowingly hire unauthorized immigrants. It also legalized certain undocumented immigrants who were seasonal agricultural workers and increased funding for the Border Patrol.

- According to economists Pia Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny, two experts who have researched this issue extensively, “IRCA sought to stem future unauthorized inflows by making it illegal to hire undocumented immigrants; requiring employers to verify workers’ eligibility; increasing funding for border enforcement; and creating the H-2A and H-2B programs for temporary agricultural and non-agricultural foreign workers, respectively.”

How did IRCA affect flows of undocumented immigrants in practice?

- Based on data collected by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) on the number of apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border, Orrenius and Zavodny find that illegal crossings declined by 11% during the period immediately after IRCA was passed, but before the period for filing amnesty applications began (November 1986-April 1987).

- However, the number of apprehensions increased again during the filing period (May 1987-April 1988), reaching levels similar to those observed before IRCA became law.

- All in all, IRCA did not substantially affect inflows of undocumented immigrants. In other words, because apprehensions did not increase during the filing period—as would be the case if people were coming to the country to apply for the program fraudulently—Orrenius and Zavodny conclude that amnesty programs do not encourage illegal immigration.

- In fact, IRCA contributed to the reduction of unauthorized migration in the short term. It also did not encourage illegal immigration in the long run in the hope of another amnesty. However, it failed to discourage illegal immigration in the long run.

Why did IRCA fail in curbing illegal immigration in the long run?

- It is broadly agreed that IRCA failed to provide realistic and workable channels for future legal immigration flows. For the majority of undocumented immigrants who entered the country after IRCA, there was no line available and the regular channels did not include them. The total number of green cards available for all lower-skilled workers is, under the current system, limited to 5,000 per year for the entire United States. This grossly insufficient number of green cards in these types of jobs is the crux of the illegal immigration problem in the United States.

- Within the current legal system, temporary visas have become the main pathway for fulfilling changing labor market needs. For lower-skilled occupations the two main visa categories are H-2A (for temporary agricultural workers) and H-2B (for temporary non-agricultural jobs). The temporary visa system has been broadly criticized, among other reasons, for its restriction on workers’ mobility. Additionally, the adjustment from temporary to permanent status is highly uncertain and bureaucratic.

- The demand for workers in the service sectors has grown considerably while the supply of available U.S. workers has steadily diminished. This is especially true in industries such as construction, food service, and agriculture, where the foreign-born represent approximately 20 percent of all workers.

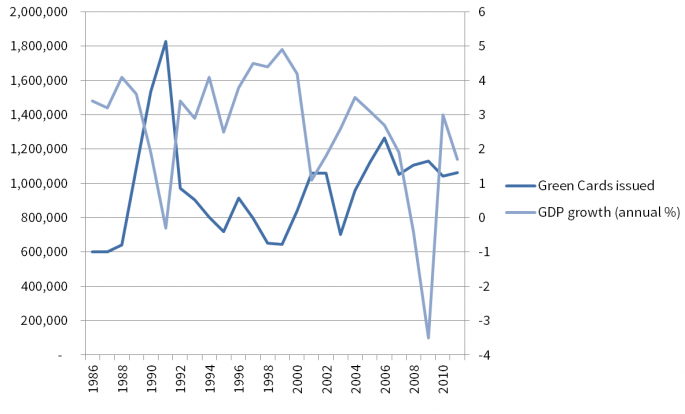

- Since 1986, the legal immigration system has not been in line with the business cycle, and, therefore, with the country’s labor needs (see Fig. 1). In other words, the rigid structure of the legal immigration system did not allow it to adjust the number and types of new admissions either in periods of economic growth or in periods of economic recession.

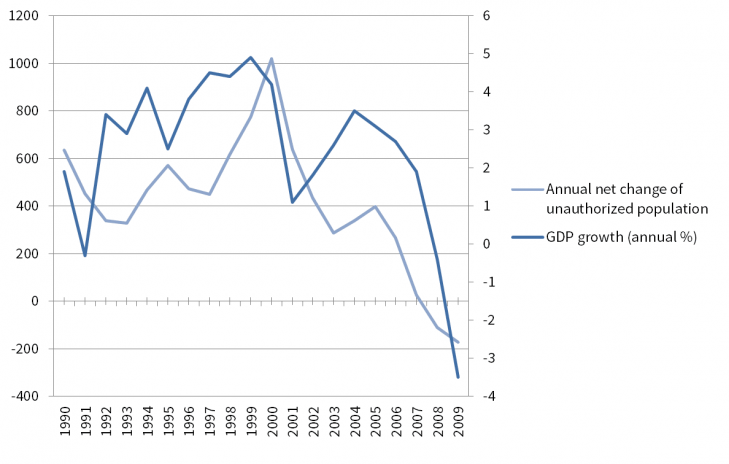

- On the other hand, the changes in unauthorized migration have to a great extent followed the fluctuations in the economy (see Fig. 2).

- All in all, IRCA failed to anticipate the economic needs of the country. As Orenius and Zavodny assert, “to ensure a supply of low-skilled workers when the economy is growing, the United States needs better temporary foreign worker programs. Most unauthorized immigrants enter to work, and surely they would prefer to enter legally.”

- In the absence of realistic legal avenues for employers to hire immigrant workers, illegal immigration continued to fill the gap when demand was high.

Figure 1: Number of green cards issued and gross domestic product growth by year

Sources: Department of Homeland Security, 2011 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Office of Immigration Statistics, September 2012; and The World Bank national accounts data.

Figure 2: Net change of unauthorized population and gross domestic product growth by year

Sources: Robert Warren and John Robert Warren. “Unauthorized Immigration to the United States: Annual Estimates and Components of Change, by State, 1990 to 2010,” International Migration Review, early view, Spring 2013: 1-34. ; and The World Bank national accounts data.

- With jobs readily available, employer sanctions not regularly enforced, and family members and immigrant communities already established and well equipped to provide assistance to newcomers, unauthorized workers kept coming. In this context, an effective solution to the issue of illegal immigration would entail acting in various fronts simultaneously. As stated by Orrenius and Zavodny, “to break the pattern of illegal immigration, a legalization program has to include a way to lower the demand for unauthorized workers while bolstering access to legal foreign workers.”

- In addition to the problems with employment-based immigration, IRCA and subsequent legislation failed to anticipate family-based immigration needs, which have since become unworkable. Under current law, there are numerical limits on most family categories, with demand typically higher than the number of available green cards. This has resulted in significant backlogs for aspiring immigrants from certain countries. In particular, some relatives of U.S. citizens or Legal Permanent Residents (LPRs) from countries like Mexico do not have a real chance of getting a green card through family ties, which may have spurred illegal immigration in some cases.

- In sum, IRCA and subsequent laws failed to provide some immigrants (in particular, those with less skills or relatives of U.S. citizens or LPRs from certain countries) the mechanisms and, therefore, the right structure of incentives to allow them to come to the country legally and to dissuade them from coming illegally. As we know, there are countless risks and dangers involved in crossing the border illegally or living in the United States unlawfully. However, as the U.S. economy created new jobs and the Mexican economy struggled—in part due to the deleterious effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—the incentives to migrate outweighed the risks. In addition, the desire to reunite with family members in the United States also contributed to this phenomenon. In the absence of workable legal channels available, undocumented migration became the norm.

How is S.744 different from IRCA?

- Unlike IRCA, S.744 couples the legalization component (which, aside from bringing millions of people out of the shadows, would result in a net benefit for the U.S. economy) with an enhanced and flexible system of rules for future immigration flows.

1. Through the new W visa, the bill creates stronger channels for lower-skilled workers when the economy is growing.

- Central to the proposed immigration system is the creation of a new nonimmigrant visa for lower-skilled workers called the W visa. Under the provisions of the bill, a new statistical agency will be created within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to regulate the W visa program. This new agency, called the Bureau of Immigration and Labor, will determine the annual cap for W visas, and will determine the list of recruitment methods employers may use. It will also conduct surveys to assess shortages in occupations by job zones, and conduct studies on employment-based visa programs. The Bureau will make annual recommendations to Congress in order to improve such programs.

- Spouses and minor children of W visa holders will be admitted to the U.S. for the same period as the visa holder and will be given work authorization. This solution is critical to ensuring that dependents have the opportunity to incorporate into the formal economy. By easing family unification, this provision also minimizes the likelihood of undocumented immigration of family members of W visa holders.

- The W visa program is a promising way to link the future immigration flows to the needs of the economy. In other words, it will absorb needed future flows of labor supply into legal channels.

2. The bill will clear the system backlog.

Under track two of the merit-based system, the bill also provides mechanisms to clear the backlog of pending visas. In particular, an alien who is a beneficiary of a petition for an employment-based or family-based immigrant visa and who has not been awarded a visa in 5 years after the petition was filed is eligible for a visa under the track two of the merit-based system. This will provide applicants with clear expectations in terms of the time they will have to wait in order to enter the country through legal channels.

3. Half of the merit based visas in the new point system will be allocated to lower skilled immigrants.

After enactment of the bill, between 60,000 and 125,000 visas will be available each fiscal year for immigrants in high-demand tier-2 occupations (1 of the 5 occupations for which the highest numbers of positions were sought to become registered positions by employers during the previous fiscal year) or in an occupation that requires little or no preparation. The initial threshold of 60,000 visas will increase by 5% per year if demand exceeds supply in any year where unemployment is under 8.5%. This will allow workers who currently do not have a real chance to get a green card to access LPR status in the future. This is important considering that the country needs immigrants at all skill levels.

4. The cap for employment-based immigrant visas allocated to “other workers” will be raised.

In the current system, only 5,000 visas are available for “other workers”—namely, persons capable of filling permanent positions that require less than two years of training or experience. These visas are part of a larger pool of visas called Employment-Based Category 3 (EB-3), which also includes visas for skilled workers and professionals. S.744 raises the cap for EB-3 from 28.6 percent to 40 percent of the worldwide employment-based level. At the same time, it removes the cap for the EB-3 “other worker” subcategory. Although the way in which visas will be allocated in practice among the different subcategories of EB-3 is yet to be seen, this change creates an opening for a much-needed solution regarding the legal incorporation of less-skilled immigrants.

5. A positive change in some family quotas: Spouses and minor children of LPRs will have an expedited process.

Because the bill reclassifies spouses and minor children of LPRs as immediate relatives, these family categories will not be subject to annual quotas anymore. This will provide relief to people who, under current law, have to wait “in line” for a long period of time in order to legally bring their immediate relatives to the country. Although partial, this is a first step in addressing some family unification issues. Consequently, this proposed change would serve as an additional incentive to avoid illegal immigration based on family separation issues.

6. The bill contains strong mechanisms for border and interior enforcement as part of a much larger and more comprehensive policy solution.

As we learned from the experience of the last two decades, enforcement-only is not a good policy solution to prevent illegal immigration. In fact, since the enactment of IRCA in 1986, the federal government has spent an estimated $186.8 billion on immigration enforcement. Yet during that time, the unauthorized population has tripled in size to 11 million. On the other hand, the new Senate bill has strong border and interior enforcement provisions (including E-Verify); but this time around they are part of a more comprehensive approach.

Conclusion

The scenario designed by S.744 regarding future migration flows is radically different from the one created by IRCA. In particular, the new Senate bill includes mechanisms to assure that future flows of immigrants (a) are absorbed through legal channels; (b) respond to the needs of the economy; (c) embrace (at least to some extent) family unification; and (d) have the flexibility to adapt to different scenarios in the future. While the system could be more generous and comprehensive, it nonetheless creates a reasonable expectation that workers who want to come to the U.S. will have an opportunity to do so legally. As these programs are implemented, careful attention to how well the various demand-based calculators are working is essential—if anything, the bill should do more to track and monitor the ability of the new scheme overall to respond quickly to market and other demands. We must carefully monitor the impact of the new system on particular groups, such as women and those who work in the informal economy. However, the solutions proposed in the bill are a significant leap forward and offer much stronger mechanisms and incentives for potential immigrants to use legal channels.

Help us fight for immigration justice!

The research is clear – immigrants are more likely to win their cases with a lawyer by their side. But very few can get attorneys.

Introducing the Immigration Justice Campaign Access Fund.

Your support sends attorneys, provides interpreters, and delivers justice.

Immigration Justice Campaign is an initiative of American Immigration Council and American Immigration Lawyers Association. The mission is to increase free legal services for immigrants navigating our complicated immigration system and leverage the voices and experiences of those most directly impacted by our country’s immigration policies to inform legal and advocacy strategies. We bring together a broad network of volunteers who provide legal assistance and advocate for due process for immigrants with a humane approach that includes universal legal representation and other community-based support for individuals during their immigration cases.